Denis Goddard on Capitol Access argues that the dollar is collapsing, and we're headed toward hyperinflation:

This comes after

a variety of predictions of hyperinflation over the last few years, none of which have panned out. I don't think this one will, either.

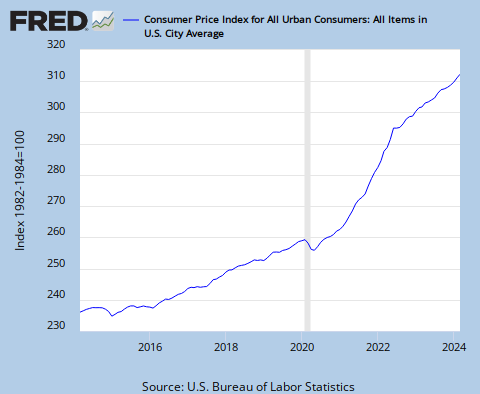

First, the data. Here is the Consumer Price Index, which measures inflation:

The trend over the last year or so should be taken with a grain of salt, because the CPI includes the prices of goods, such as gas and food, which vary greatly in response to changes in, for example, the weather or international politics. The core CPI, which excludes the more variable prices and is therefore a better measure of long-term inflationary trends, shows lower inflation than this graph. I'm showing the more inclusive, volatile CPI only because I don't want to be accused of underestimating inflation. (The Boston Fed has recently released

research confirming that commodity prices do not predict long-term inflation.)

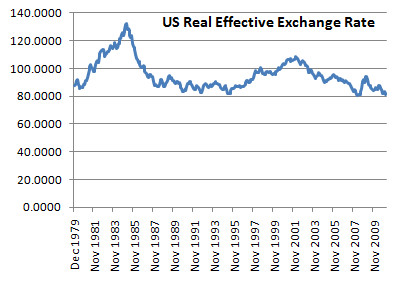

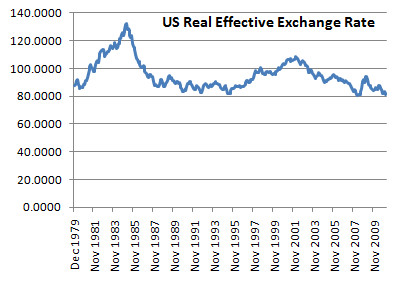

Here is the value of the dollar relative to other currencies:

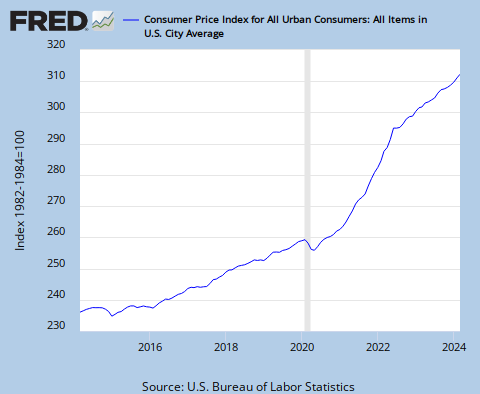

Here is the interest payed on 10-year treasury bonds:

This suggests that the bond market expects inflation over the next 10 years to be a whopping 3.46%, or even less. [Edit: Unless real interest rates are negative, which is possible. However, we can use the interest payed on

inflation-indexed bonds to estimate the real interest rate, and the latest figure is .86%. The difference between the two rates, the "spread", should approximately equal expected inflation. This suggests an expectation of 2.6% inflation over the next 10 years— shockingly low.]

None of these measures looks especially frightening. And the situation is unlikely to deteriorate, for multiple reasons.

First, the Fed is well prepared to fight inflation. If inflation starts rising significantly, it can sell some of its

$2.7 trillion worth of assets for dollars, reducing the money supply. And thanks to the way fractional reserve banking works, when the Fed removes currency this way, the effect is

multiplied, so that removing $2.7 trillion dollars shrinks the money supply by much more than $2.7 trillion. Taking money out of the economy also increases interest rates, which is what commentators usually refer to.

The Federal Reserve famously used this strategy in 1980 and '81 to eradicate the high inflation of the 1970s. In fact, it was so successful that the disinflationary pressures caused

a recession. (Though preventing inflation is much easier than reducing it, so we needn't worry about another Fed-induced recession.)

The Fed can also raise reserve requirements for banks. This would lower the money multiplier, which would lower the money supply. And, as of 2008, the Fed can pay banks interest on their

excess reserves— basically, pay them to not lend out money— which allows the Fed to more easily fine-tune inflation rates and the money supply.

Besides the Federal Reserve, another force will likely intervene to prevent a collapse of the U.S. dollar. If the dollar drastically depreciates (that is, loses value with respect to other currencies), the European Central Bank will probably expand the supply of Euros in an attempt to stabilize exchange rates. Why? Because, if the dollar depreciates, American goods become cheaper, and European goods become relatively more expensive, leading to higher American exports and lower European exports. This would harm the European economy. (In fact, the European Central Bank is

already responding this way.) Other U.S. trading partners face the same incentives.

So probably no currency collapse any time soon.

(Hat tip to

Dean Baker and

Paul Krugman, and

Paul Krugman again, for some data and arguments.)