This comes after a variety of predictions of hyperinflation over the last few years, none of which have panned out. I don't think this one will, either.

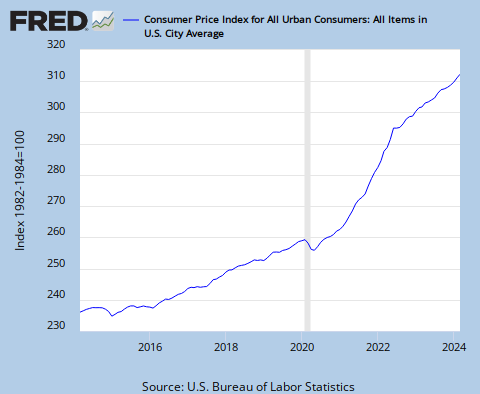

First, the data. Here is the Consumer Price Index, which measures inflation:

The trend over the last year or so should be taken with a grain of salt, because the CPI includes the prices of goods, such as gas and food, which vary greatly in response to changes in, for example, the weather or international politics. The core CPI, which excludes the more variable prices and is therefore a better measure of long-term inflationary trends, shows lower inflation than this graph. I'm showing the more inclusive, volatile CPI only because I don't want to be accused of underestimating inflation. (The Boston Fed has recently released research confirming that commodity prices do not predict long-term inflation.)

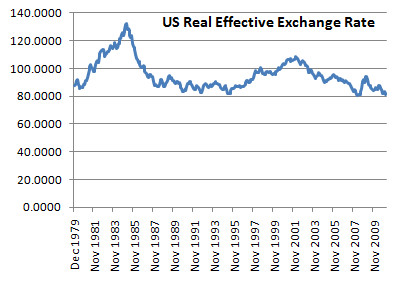

Here is the value of the dollar relative to other currencies:

Here is the interest payed on 10-year treasury bonds:

This suggests that the bond market expects inflation over the next 10 years to be a whopping 3.46%, or even less. [Edit: Unless real interest rates are negative, which is possible. However, we can use the interest payed on inflation-indexed bonds to estimate the real interest rate, and the latest figure is .86%. The difference between the two rates, the "spread", should approximately equal expected inflation. This suggests an expectation of 2.6% inflation over the next 10 years— shockingly low.]

None of these measures looks especially frightening. And the situation is unlikely to deteriorate, for multiple reasons.

First, the Fed is well prepared to fight inflation. If inflation starts rising significantly, it can sell some of its $2.7 trillion worth of assets for dollars, reducing the money supply. And thanks to the way fractional reserve banking works, when the Fed removes currency this way, the effect is multiplied, so that removing $2.7 trillion dollars shrinks the money supply by much more than $2.7 trillion. Taking money out of the economy also increases interest rates, which is what commentators usually refer to.

The Federal Reserve famously used this strategy in 1980 and '81 to eradicate the high inflation of the 1970s. In fact, it was so successful that the disinflationary pressures caused a recession. (Though preventing inflation is much easier than reducing it, so we needn't worry about another Fed-induced recession.)

The Fed can also raise reserve requirements for banks. This would lower the money multiplier, which would lower the money supply. And, as of 2008, the Fed can pay banks interest on their excess reserves— basically, pay them to not lend out money— which allows the Fed to more easily fine-tune inflation rates and the money supply.

Besides the Federal Reserve, another force will likely intervene to prevent a collapse of the U.S. dollar. If the dollar drastically depreciates (that is, loses value with respect to other currencies), the European Central Bank will probably expand the supply of Euros in an attempt to stabilize exchange rates. Why? Because, if the dollar depreciates, American goods become cheaper, and European goods become relatively more expensive, leading to higher American exports and lower European exports. This would harm the European economy. (In fact, the European Central Bank is already responding this way.) Other U.S. trading partners face the same incentives.

So probably no currency collapse any time soon.

(Hat tip to Dean Baker and Paul Krugman, and Paul Krugman again, for some data and arguments.)

The adjunct scholar of the Mises Institute, among others, begs to differ. Your reliance on the CPI (an imaginary number based on assumptions made by -- surprise, surprise! -- a government agency) is the fly in your ointment.

ReplyDeletehttp://is.gd/OBbK0z

One place inflation is "hiding" is in groceries. The manufacturers have been reducing the amount of goods in their packages and keeping the prices relatively the same.

http://is.gd/AYtv67

As for the Fed's "assets", any such sales entirely depend on whether anyone is willing to buy.

On the Euro issue, that scenario doesn't consider what happens if the Euro fails first.

The sad truth is that Mises.com is all fake economics. No one there cares about reality, the conclusions are already known. All that's needed is a serious-sounding excuse to believe the Rothbard-given truth. (Rationalizing, not rationality.) It's not even real Austrian economics.

ReplyDeleteAbout the CPI in real life:

http://www.slate.com/id/2278623/

(Smaller packages can't hide from the CPI.)

Are you predicting that people will stop buying bonds in the near future? How much do you want to bet?

Are you predicting that the Euro will collapse in the near future? How much would you like to bet?

Will, thank you so much for taking the time to post this analysis. Of course, I respectfully disagree with the conclusion.

ReplyDelete1) The charts you use to back up your position show the highest price inflation, and the lowest value of the US dollar, in the duration of the chart.

2) The assertion that "If inflation starts rising significantly, [the Fed] can sell some of its $2.7 trillion worth of assets for dollars"

I disagree. Most of those assets are "toxic" assets that the Fed bought precisely because they were *not* marketable.

3) "The Fed can also raise reserve requirements for banks"

Only if it wants to bankrupt them. The banks are making great profits now, but only via the effectively free money they get from the Fed.

[Mises.org, I should have said.]

ReplyDeleteDoesn't surprise me that you disagree.

1) I think we're at the highest CPI value about 95% of the time.

2) They can always lower the price.

3) Raising reserve requirement wouldn't bankrupt banks. Banks would raise the price of loans-- charge higher interest rates-- to make up for it.

Well, just as you dimiss the Mises Institute out of hand as "not real economics" without rebutting their conclusions, I dismiss the veracity and reliability of the CPI as "not real numbers".

ReplyDeleteAnd yes, with S&P's still fairly recent negative outlook on bonds combined with their worthlessness as an investment as compared to other, stronger investment opportunities, I expect their sales to decline exponentially over the next 24 months as the economy moves closer to tanking completely.

http://is.gd/QRJLgk

I invite you to read It's the End of The Dollar As We Know It by John Butler, Managing Director and Head of the Index Strategies Group at Deutsche Bank in London.

Thanks, Zeus, for the link to dailyreckoning. I had never seen that site before. I like it.

ReplyDeleteZeus:

ReplyDeleteIn regards to the CPI, good for you.

In regards to bonds, you're forgetting that the return changes in response to supply and demand. A prediction which doesn't take that into account is useless. And "over the next 24 months" is a pretty major step backwards from Denis' "immediately". Plus, the interest rates on bonds are pretty low (3.25%), which is really, really bizarre if investors think they're a worthless investment.

Though I have a few disagreements with Butler's analysis, my big counterarguments have already been posted as the blog.

@Denis

ReplyDeleteIts a good site. They have few good books worth checking out as well. Also, they are the creators of the documentary film and book of the same name, I.O.U.S.A. starring former comptroller general, David Walker.

@Skeptikos

Bonds:

Demand requires trust and even the biggest, long-time buyers are running out of faith, especially in paper assets. There are far more profitable investment opportunities available to them than interest-bearing IOU's that might never pay out.

24 Months:

Well, I don't know what Denis had predicted but I'm being cautious -- perhaps even hopeful -- when I say 24 months. I want to say 12, however, the Fed has surprised me before at its ability to drag out the inevitable correction -- far longer than I'd imagined possible.

But as they say, nothing lasts forever.

May 2012, and it hasn't hit the fan yet.

ReplyDeleteI give it another 12-24 months, tops.